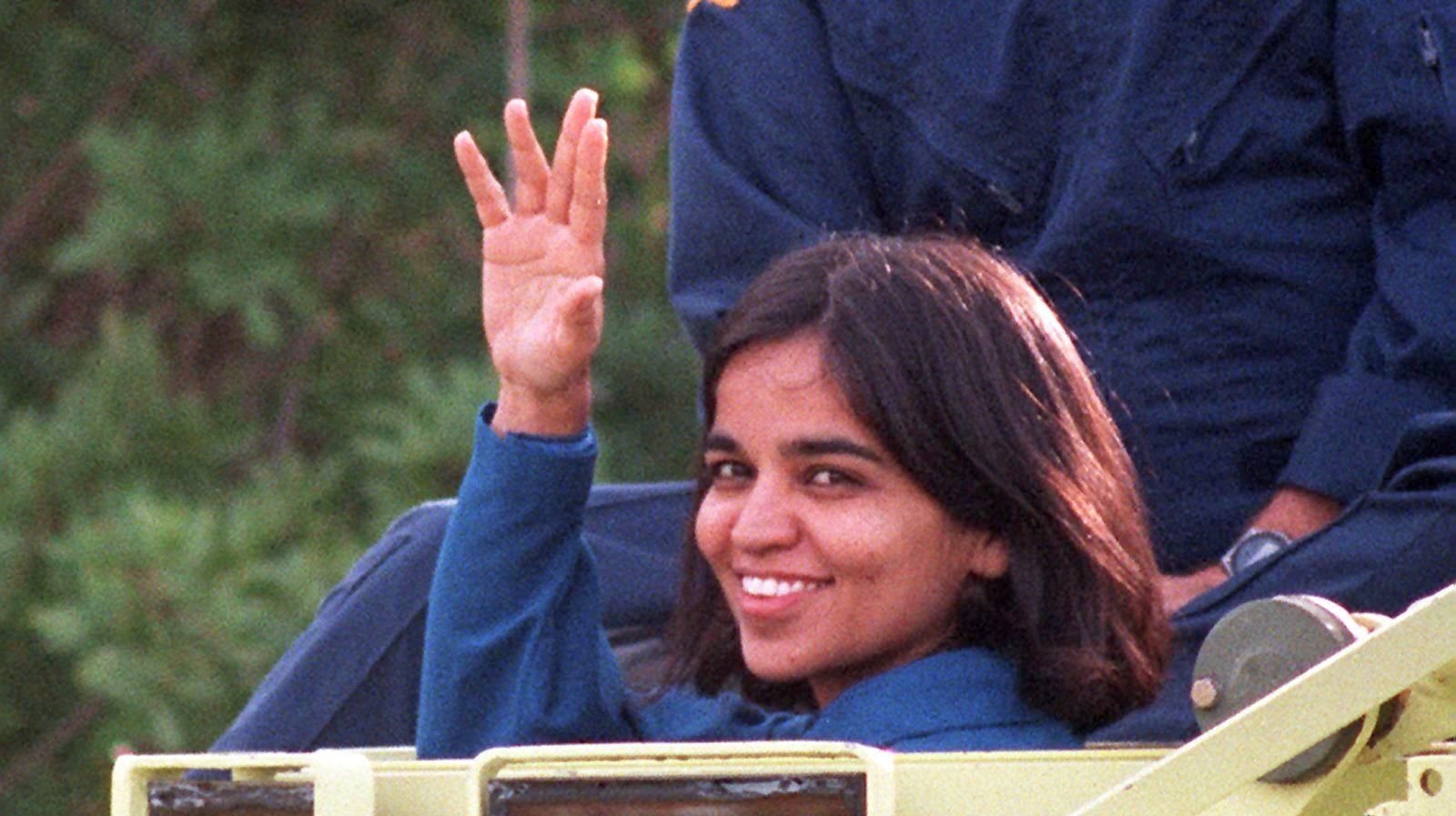

Kalpana Chawla

“You are just your intelligence.”

Early life and education

Kalpana Chawla was born on 17 March 1962 in Karnal, Haryana.[11] She completed her schooling from Tagore Baal Niketan Senior Secondary School, Karnal. Growing up, Chawla went to local flying clubs and watched planes with her father.[12] After earning a Bachelor of Engineering degree in Aeronautical Engineering from Punjab Engineering College, India, Chawla moved to the United States in 1982 and obtained a Master of Science degree in Aerospace Engineering from the University of Texas at Arlington in 1984.[13] She went on to earn a second Master's in 1986 and a PhD[14] in aerospace engineering in 1988 from the University of Colorado Boulder.[15][16]

Career

In 1988, Chawla began working at NASA Ames Research Center, where she did computational fluid dynamics (CFD) research on vertical and/or short take-off and landing (V/STOL) concepts. Much of Chawla's research is included in technical journals and conference papers. In 1993, she joined Overset Methods, Inc. as vice president and Research Scientist specializing in simulation of moving multiple body problems. Chawla held a Certified Flight Instructor rating for airplanes, gliders and Commercial Pilot licenses for single and multi-engine airplanes, seaplanes and gliders. After becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen in April 1991, she applied for the NASA Astronaut Corps.[17] Chawla joined the corps in March 1995 and was selected for her first flight in 1997.

First space mission

Chawla's first space mission began on 19 November 1997, as part of the six-astronaut crew that flew the Space Shuttle Columbia flight STS-87. Chawla was the first Indian woman to go in space. She spoke the following words while traveling in the weightlessness of space: "You are just your intelligence." Chawla had traveled 10.67 million km, as many as 252 times around the Earth. On her first mission, Chawla traveled 10.4/6.5 million miles in 252 orbits of the earth, logging more than 376 hours (15 days and 16 hours) in space.[18][7] During STS-87, she was responsible for deploying the Spartan Satellite which malfunctioned, necessitating a spacewalk by Winston Scott and Takao Doi to capture the satellite. A five-month NASA investigation exonerated [19] Chawla by identifying errors in software interfaces[20] and the defined procedures of the flight crew and ground control. After the completion of STS-87 post-flight activities, Chawla was assigned to technical positions in the astronaut office to work on the space station.

Second space mission and death

In 2000, Chawla was selected for her second flight as part of the crew of STS-107. This mission was repeatedly delayed due to scheduling conflicts and technical problems such as the July 2002 discovery of cracks in the shuttle engine flow liners. On 16 January 2003, Chawla finally returned to space aboard Space Shuttle Columbia on the ill-fated STS-107 mission. The crew performed nearly 80 experiments studying Earth and space science, advanced technology development, and astronaut health and safety.

During the launch of STS-107, Columbia's 28th mission, a piece of foam insulation broke off from the Space Shuttle external tank and struck the port wing of the orbiter. Previous shuttle launches had seen minor damage from foam shedding,[21] but some engineers suspected that the damage to Columbia was more serious. NASA managers limited the investigation, reasoning that the crew could not have fixed the problem if it had been confirmed.[22]

When Columbia re-entered the atmosphere of Earth, the damage allowed hot atmospheric gases to penetrate and destroy the internal wing structure, which caused the spacecraft to become unstable and break apart.[23] After the disaster, Space Shuttle flight operations were suspended for more than two years, similar to the aftermath of the Challenger disaster. Construction of the International Space Station (ISS) was put on hold; the station relied entirely on the Russian Roscosmos State Corporation for resupply for 29 months until Shuttle flights resumed with STS-114 and 45 months for crew rotation.

Chawla died on 1 February 2003, in the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster, along with the other six crew members, when Columbia disintegrated over Texas during re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere, shortly before it was scheduled to conclude its 28th mission, STS-107.[24] Her remains were identified along with those of the rest of the crew members and were cremated and scattered at Zion National Park in Utah in accordance with her wishes.[25]

Honours and recognition

The fourteenth contracted Northrop Grumman Cygnus spacecraft mission delivering supplies to the ISS was named the S.S. Kalpana Chawla after her.[26][27][28]

Asteroid 51826 Kalpana Chawla, one of seven named after the Columbia's crew[29]

The lunar crater Chawla is named after Kalpana Chawla.[30]

On 5 February 2003, the Prime Minister of India at the time, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, announced that a meteorological series of satellites, MetSat, was to be renamed "Kalpana 1". The first satellite of the series, "MetSat-1", launched by India on 12 September 2002, was renamed "Kalpana-1".[31]

74th Street in the "Little India" of Jackson Heights, Queens, New York City, New York, United States, has been renamed "Kalpana Chawla Way" in her honor.[8]

In honor of her, a street was named Kalpana Chawla Street in Rayon Nagar in Sirumugai, a village in Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India.

The Kalpana Chawla Award was instituted by the Government of Karnataka in 2004 to recognize young women scientists.[32]

One of Florida Institute of Technology's student apartment complexes, Columbia Village Suites, has halls named after each of the astronauts, including Chawla.

The NASA Mars Exploration Rover mission has named seven peaks in a chain of hills, named the Columbia Hills, after each of the seven astronauts lost in the Columbia shuttle disaster. One of them is Chawla Hill, named after Chawla.

Steve Morse from the band Deep Purple created the song "Contact Lost" in memory of the Columbia tragedy. Chawla knew Morse and took the band's Machine Head, featuring the song "Space Truckin'" with her on the mission. Morse's tribute song can be found on the album Bananas.[34]

Novelist Peter David named a shuttlecraft, the Chawla, after the astronaut in his 2007 Star Trek novel, Star Trek: The Next Generation: Before Dishonor.[35]

The Kalpana Chawla ISU Scholarship fund was founded by alumni of the International Space University (ISU) in 2010 to support Indian women's participation in international space education programs.[36]

The Kalpana Chawla Memorial Scholarship program was instituted by the Indian Students Association (ISA) at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) in 2005 for meritorious graduate students.[37]

The Kalpana Chawla Outstanding Recent Alumni Award at the University of Colorado, given since 1983, was renamed after Chawla.[38]

The University of Texas at Arlington, where Chawla obtained a Master of Science degree in aerospace engineering in 1984, opened a dormitory named Kalpana Chawla Hall in 2004.[39]

Kalpana Chawla Hall, University of Texas Arlington

In addition, the university dedicated the Kalpana Chawla Memorial on 3 May 2010, in Nedderman Hall, one of the primary buildings in the College of Engineering.[40]

The girls' hostel (what a university dormitory is called in India) at Punjab Engineering College is named after Chawla. In addition, an award of INR twenty-five thousand, a medal, and a certificate is instituted for the best student in the Aeronautical Engineering department.[41]

The Government of Haryana established the Kalpana Chawla Planetarium in Jyotisar, Kurukshetra.[10]

The Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur, named the Kalpana Chawla Space Technology Cell in her honor.[9][42]

Delhi Technological University named a girls' hostel block after Chawla.[43]

A military housing development at Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland, has been named Columbia Colony and includes a street named Chawla Way.

A hostel block in Pondicherry University has been named after Chawla.[44]

Kalpana Chawla Government Medical College (KCGMC) is a Medical college located in Karnal, Haryana, India named after Chawla. Kalpana was born in Karnal.

The National Institute of Technology, Kurukshetra named a girls' hostel after Chawla.

The Orissa University of Technology & Research (OUTR), Bhubaneswar named a girls' hostel after Chawla.

The National Institute of Technology, Bhopal named a girls' hostel Kalpana Chawla Bhawan.[45]

On 1 April 2022, a satellite named after Chawla (ÑuSat 24 or "Kalpana", COSPAR 2022-033X) was launched into space as part of the Satellogic Aleph-1 constellation.

Private life

On 2 December 1983, Kalpana Chawla was married to Jean-Pierre Harrison at the age of 21.[15] After the Columbia disaster, Harrison was approached by filmmakers to make a movie on Chawla's life, but he refused because he prefers to keep their life private.[46]

In popular culture

Mega Icons (2018–2020), an Indian documentary television series on National Geographic about prominent Indian personalities, dedicated an episode to Chawla's achievements.[47]

About Space Shuttle Columbia

Space Shuttle Columbia (OV-102) was a Space Shuttle orbiter manufactured by Rockwell International and operated by NASA. Named after the first American ship to circumnavigate the upper North American Pacific coast and the female personification of the United States, Columbia was the first of five Space Shuttle orbiters to fly in space, debuting the Space Shuttle launch vehicle on its maiden flight in April 1981. As only the second full-scale orbiter to be manufactured after the Approach and Landing Test vehicle Enterprise, Columbia retained unique features indicative of its experimental design compared to later orbiters, such as test instrumentation and distinctive black chines. In addition to a heavier fuselage and the retention of an internal airlock throughout its lifetime, these made Columbia the heaviest of the five spacefaring orbiters; around 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds) heavier than Challenger and 3,600 kilograms (7,900 pounds) heavier than Endeavour. Columbia also carried ejection seats based on those from the SR-71 during its first six flights until 1983, and from 1986 onwards carried an imaging pod on its vertical stabilizer.

During its 22 years of operation, Columbia was flown on 28 missions in the Space Shuttle program, spending over 300 days in space and completing over 4,000 orbits around Earth. While it was seldom used after completing its objective of testing the Space Shuttle system, and its heavier mass and internal airlock made it less than ideal for planned Shuttle-Centaur launches and dockings with space stations, it nonetheless proved useful as a workhorse for scientific research in orbit following the loss of Challenger in 1986. Columbia was used for eleven of the fifteen flights of Spacelab laboratories, all four United States Microgravity Payload missions, and the only flight of Spacehab's Research Double Module. The Extended Duration Orbiter pallet was used by the orbiter in thirteen of the pallet's fourteen flights, which aided lengthy stays in orbit for scientific and technological research missions. Columbia was also used to retrieve the Long Duration Exposure Facility and deploy the Chandra observatory, and also carried into space the first female commander of an American spaceflight mission, the first ESA astronaut, the first female astronaut of Indian origin, and the first Israeli astronaut.

At the end of its final flight in February 2003, Columbia disintegrated upon reentry, killing the seven-member crew of STS-107 and destroying most of the scientific payloads aboard. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board convened shortly afterwards concluded that damage sustained to the orbiter's left wing during the launch of STS-107 fatally compromised the vehicle's thermal protection system. The loss of Columbia and its crew led to a refocusing of NASA's human exploration programs and led to the establishment of the Constellation program in 2005 and the eventual retirement of the Space Shuttle program in 2011. Numerous memorials and dedications were made to honor the crew following the disaster; the Columbia Memorial Space Center was opened as a national memorial for the accident, and the Columbia Hills in Mars' Gusev crater, which the Spirit rover explored, were named after the crew. The majority of Columbia's recovered remains are stored at the Kennedy Space Center's Vehicle Assembly Building, though some pieces are on public display at the nearby Visitor Complex.